I was reading few days back on beirutspring an article written by an Egyptian Journalist called Ahmed Ramadan on winemaking in Lebanon and why Lebanese drink more alcohol than other Arabs.

In the first paragraph of the article, the author assumes that Lebanon is a Muslim country and that unlike other Muslim societies, it allows advertising drinking, serving and buying alcohol. Someone should remind this guy Lebanon is NOT a Muslim state and abides by a constitution written by both Christians and Muslims where each citizen can freely practice his beliefs.

In an region where Islam prevails, winemaking can be a failing trade. It’s well-known that Muslims are prohibited from drinking, serving, selling and buying alcohol. Some Arab societies frown upon alcohol consumption and look down on those who enjoy a glass of wine or a bottle of beer.

He continues his primary false statement with another absurd one, that claims that Lebanese drink “due to the civil wars and financial woes that have broken the heart of the capital” and as “an escape in the form of fun times.” Well Mr.Ramadan, i assure you that most of us drink because we enjoy alcohol and don’t consider it as an evil thing. We have a great local beer and great local wines and we drink them the same way most Egyptians like their Shishas.

Last but not least, if there’s anyone that drinks in Lebanon out of frustration and to escape the restrictions set by their local governments, they’re many Arab tourists coming from all over the Arab countries, including Egypt.

PS: If i were Ksara, i would have asked this author to correct those false allegations about Lebanon and the Lebanese as this article is bad publicity for them.

But Lebanon is a Muslim nation (more than 50% are Muslims) as much as Turkey is a Muslim nation (Secular constitution). The real sad parts is you still have very closed minded journos from the Middle East judging by Middle Ages standards… The journalist seems to deal with a very noble and sophisticated subject as a despicable issue because it is treated as such by the predominant religion in the region. It is not about Christians and Muslims (even though the writer brings shoves religion right into our face stating that alcohol is banned by a specific religion), rather it is about appreciating the good things in Life! How can somebody writes about wine and did not try wine because it is banned by his god?

For me, I will take a drink (alcoholic drink that is) any-day over listening to religion(any religion) cheers to that!

It’s just a badly written article, in bad English I mean

The reporter obviously has not visited Dubai Airport’s duty free, or any of its bars and clubs, nor has he seen the big ads for Penfold’s wine at Dubai airport

Most Arab/Muslim countries have alcohol, the ones that don’t are the sad exceptions

Devin,

Lebanon does not follow shariaa as its constitution therefore is not a Muslim country. Christians and Muslims regardless of their numbers have equal political rights and representation. This is what made and still makes Lebanon a free country compared to its neighbors.

I really want to visit Lebanon. Is it safe?

Actually, the journalist who wrote the article seems to have no knowledge of history. Alcohol is actually an important part of Arab history, even though the Moslem faith is against it! below is an article I cut and paste from the Economist 2003 Christmas issue.

Arak

Liquid fire

The Arabs discovered how to distil alcohol. They still do it best, say some

Dec 18th 2003 | BEIRUT

WHAT is Islam’s greatest gift to the world? The faith of the Koran, Muslims will promptly say—along, some would add, with the Arabic language. Yet it may be that the single most pervasive legacy of Islamic civilisation is not holy scripture, but the rather unholy art of distilling alcohol. Not only were Arabs the first to make spirits. The great trading civilisation of Islam spread the skill across the globe, and in its lands some of the world’s finest alcoholic concoctions are still made to this day.

Although the delights of fermented drink were known to cavemen, the natural alcohol content of primitive wines and beers would not top 16%. Yet early China and Egypt both discovered techniques of distillation that might, if applied to such brews, have stiffened their potency. Later, Aristotle described a way of vaporising salt water into fresh, the Romans distilled turpentine from pine oil, and two Alexandrian ladies in the first centuries after Christ, Mary the Jewess and Hypatia, invented devices for separating liquids by heating them. Yet, oddly, nobody in the ancient world at this time seems to have exploited the different boiling-points of alcohol and water to concentrate weak wine into stronger spirits (though some historians assert that the Indians made a fortified beer this way, in or around 800BC).

An explanation may lie in the fact that alcohol, when distilled from fermented drinks, typically contains traces of poisonous methanol. Since methanol vaporises at a lower temperature than drinkable ethanol, the trick is to discard the first part of any distillation. Sadly, many prospective tipplers probably perished before the Arabs sorted out the technique. It is possible, too, that the bubbly science was set back some years by the Roman emperor Diocletian, who decreed the burning of alchemists’ manuscripts in 296AD for fear their discoveries would debase his coinage.

The book-burning was not entirely successful. Medieval Arab science took up the work of the Greeks, as the word alchemy itself suggests. (It is the Arabic article al- added to the ancient Greek kimia, which referred to the magical science of the black land of Kemet, which is to say Egypt.) Precisely when and by whom the distillation of alcohol was perfected is not known.

Some suggest that Egyptian monks did the deed some time in the sixth century. Others credit the Armenians. There is no conclusive evidence for either theory. What is known is that by the ninth century Arab authors such as Jaber bin Hayyan, an Iraqi polymath best known for elaborating al-jabr or algebra, were describing “flammable vapours†at the mouths of heated wine vessels.

His contemporary, the legendary poet and lush Abu Nawas (who died in 815AD), was less prim. In one ode, versifying over a night of revelry in a Baghdad tavern, he called for increasingly strong drink, ending the session with a liquor that was “as hot between the ribs as a firebrandâ€. The description clearly hints at something punchier than mere wine.

The etymology of distilling provides further proof of Arab origins. The word alcohol itself derives from the Arabic al-kohl, the antimony eyeliner of that name, being used by Arab alchemists to describe any “purified†substance (thus distinguishing “pure†spirits from khamr, the common word for fermented drinks that comes from khamira, the Arabic for yeast).

Alcohol is made in a still or alembic, which is yet another Arabic alchemical term, appropriated from the Greek ambix, a sort of crook-necked vessel. Such a gadget might be used for making eau de vie or aquavit, names which bear an oddly literal similarity to the maal-hayat or water of life celebrated in drinking scenes from that medieval Arabic classic “The Thousand and One Nightsâ€. Hardly surprising, considering that the first evidence of distilling in Europe comes from Sicily in the 11th century, when the island was a possession of the Fatimid caliph of Cairo.

Sweet sweat of Araby

As monkish translators of Arab science carried such terminology north and west, the art of making “burnt wine†spread across Europe in an intoxicating wave of brandies, grappas, whiskies, schnappses and vodkas. In the meantime, Arab caravans and dhows transported another pungent expression to the east. Arak, or more properly araq, is the Arabic word for sweat or perspiration. This does not refer to the sticky effect of quaffing too much booze. It is a literal description of the process of distillation. When a wine or mash is heated in an alembic, its araq collects inside the still’s long spout before dripping out as “raised†alcohol.

In Mongolia arak refers to a stiff drink distilled from fermented mare’s milk, and has done since the 14th century, as is known from a Chinese treatise that describes the arrival in the Middle Kingdom of this fiery new potion. To Goans, Sri Lankans and Balinese, the same word describes a fire-water cooked up from the sap of flowering coconuts. Tamils brew it from sugarcane, Indonesians from rice wine, thirsty Iranians from anything they can lay hands on, and get away with.

The national drinks of Turkey, Albania and Bulgaria are all known as raki. The Sudanese call their potent version aragi and, despite government-enforced religious strictures, bubble it up in home stills out of date wine or sorghum mash. In the outskirts of Mecca, Saudis secretly brew an even deadlier drink of the same name—but this home-made hooch is still a safer tipple than the methanol-laced after-shave that killed 11 desperate revellers in the holy city last year.

Arak? No phobia

For most Arabs today, arak has come to refer specifically to the aniseed-infused, wine-based liquor that is manufactured all over the Arab east, from Baghdad to Beirut. Yet it is further testimony to Arab influence that the taste for anise spirits extends across the Mediterranean and beyond. The raki that Turks call “lion’s milk†is close to the Arab original. Greek ouzo, and its stronger cousins tsikoudia and tsipouro, are aniseed araks, sometimes elaborated with mastic and other herbs.

The arak of choice—for travellers, at least

Italy’s sambuca is a sweeter version, made from witch elder and liquorice, which is drunk neat as a liqueur, but the more local mistra of the Marche region is straightforward arak, often drunk, like the original, diluted with water. The Spanish have exported their taste for such liqueurs as ojen and anisado to Latin America, where they appear in forms such as Colombia’s robust aguardiente anisado.

France, of course, has its passion for pastis. Others may find the stuff syrupy and cloying, but the French manage to swallow an astounding 75m litres a year.

Understandably, those not familiar with Levantine arak tend to assume it is much like pastis. But connoisseurs find little resemblance, beyond the fact that both are strong, taste of anise and cloud mysteriously when water is added. (The clouding is caused by emulsification of the anise oils suspended in alcohol.) Pastis is sugared, and flavoured with a range of herbs, including liquorice and star anise imported from Indochina. Its base alcohol is of the cheap variety, typically distilled from sugarbeet. It is drunk, copiously, as an afternoon aperitif.

A proper arak, by contrast, has only two ingredients, grapes and the native aniseed of the Mediterranean. It is drunk not before or after meals, but with them. The uninitiated may flinch at the notion of washing down food with a pungent spirit. But dilution with two parts of water renders arak only slightly more intoxicating than a strong wine. And because arak clears the palate more efficiently than wine, it makes the perfect accompaniment to a Middle Eastern mezze, the array of small, tasty morsels that typically includes such contrasting flavours as bitter olives, fresh almonds, spring onions, goat’s cheese, raw minced lamb, and chicken livers stewed in pomegranate juice.

Syrians, Israelis, Palestinians, Jordanians and Iraqis—at least until some Shia fanatics trashed Baghdad’s distilleries last May—have long happily quaffed their own araks. But most would concede that the best of the lot is Lebanese. Arak is not just Lebanon’s national drink. For many it is a passion, to the point that most of the arak consumed in the country is not factory-produced, but home-distilled. The residents of one typical little Maronite village in the mountainous Kesrouan region, for instance, reckon at least ten families there run their own stills.

Some home-brewers cheat, as do the makers of Lebanon’s cheaper commercial brands, by buying industrially produced ethanol and flavouring it with anise extract. The more conscientious follow traditional methods to the last detail. Elias Fadel distils just 1,000 bottles a year for the exclusive use of his family’s restaurant, Fadel, which is set on a pine-forested ridge above the town of Bikfaya. The effort is costly in time and money, but the result, he says with a gleam in his eye, is worth it.

Every September, Mr Fadel buys ten tonnes of obeidi grapes, a native Lebanese variety that is said to be an ancestor of chardonnay. Gently crushed, the grapes are left to ferment for three weeks in barrels in the restaurant’s basement. The fresh wine is then transferred to a copper still. This contraption, hand-fashioned by Muslim coppersmiths in the bazaars of Tripoli, looks unchanged from medieval models.

The first distillation, with the toxic tops and tails removed, produces a highly concentrated spirit. With fresh water having again reduced the alcohol level, precise portions of unwashed, uncrushed anise from Hineh, a village on the Syrian slopes of Mount Hermon, are steeped in the liquor before a second round in the still.

Give it the old 53rd degree

Unlike the makers of common spirits such as whiskey, Mr Fadel does not stop at a second distillation. He proceeds to a third and even a fourth, topping up the arak with water each time before bringing it down to 53 degrees of alcohol, Lebanon’s government-mandated standard. The crystal clear liquid is then matured in clay jars for at least a year. The large jars, which look just like Roman amphoras, are slightly porous. Mr Fadel reckons that with the multiple reduction of his distilling, followed by the loss of up to 15% of the arak from evaporation, his cost per bottle is about $10, not including his own labour.

This explains why Lebanon’s better commercial araks are as expensive as imported spirits. Competition, along with changes in the Lebanese way of life that have made Beirut’s long, arak-soaked lunches a rarer treat, has certainly cut into sales. (In Greece, similarly, whisky now outsells ouzo.) Yet recent years have seen a return of interest to the national drink. Whereas long-established brands, such as Ksara and Fakhra, now tout their adherence to traditional arak-making methods, newcomers have added a touch of glamour to the high end of the business.

One such is El Massaya, a fast-growing winery founded by two brothers who returned to the militia-infested Bekaa valley after sitting out Lebanon’s 1975-89 civil war in the West. “The local mayor told my father, your son has gone berserk, wanting to make alcohol here,†says Sami Ghosn. “I had to drive around with a Kalashnikov in the car.†Convinced there was a niche for ultra-traditional arak, the Ghosn brothers insisted on using vine-wood fires to heat their double-headed still, and persuaded traditional potters to come out of retirement to make their first ageing jars. El Massaya’s cellars now bulge with hundreds of arak-filled amphoras. In duty-free shops across the region, its dusky, blue-tinted bottles are the arak of choice. Sooner or later, Mr Ghosn believes, the rest of the world will catch on.

Nor Syria, Nor Egypt apply the shariah law! Does that make them secular countries even their respective constitutions are, I highly doubt so, especially for Egypt! Since they lost the civil war in the 1990 (as rectified in the taif accord) and Lebanese Christian are in denial about; it become the ultimate taboo to talk about,case in point: if I look any of my lebanese christian friends in the eye and make the statement that christian lost the war and by having a christian president will not camouflage the fact that Lebanon is a Muslim majority country. Now, Bahrain is a sunni or shia country ? go figure!

When I linked to that article , my essential critique was not with his facts or with his intentions (which in my mind seem good), but with his prejudices. He is not consciously aware of them, but his writing betrays a judgmental attitude that drinking alcohol is wrong.

And Devin, what day is the weekend in Lebanon? Sunday or Friday?

What specific day do all the ministries including the government stop functioning? Sunday or Friday?

Till u figure it out, I meanwhile enjoy my arak! Cheers!

This is funny especially that it is written by a journalist coming from a country producing more beer brands than we do and wine.

Egyptians when not able to buy alcohol drink after-shave n eau-de-cologne! So pleeeeaaaaase!

Michele,

True, I am dealing with my hangover today and it is a SUNDAY (i.e. weekend)! does that make Turkey a Christian country? spare me the denials that Lebanon is a Muslim Majority Country (No, it does not apply shariah, nor it is secular. I get that; but by the most conservative statistics 60% of Lebanese claim Islam as their religion). Enjoy your Sundays as weekends while they last!

Does turkey celebrate Xmas, Easter, n all xtian holdays as official holidays?

I can go on n on n trust me I can as well enjoy it but please let us not get there as if I’m enjoying that discussion, I don’t like seeing u frustrated!

So let’s discuss something that u n I obviously enjoy which is drinking nice cocktails n thank Lebanon for not being a retarded nation n country!

Devin,

Turkey is a secular country because Ataturk wanted it so, however since then, Turkey has been struggling to remain secular due to the rise of Islamists and pro-religious groups inside it.

Lebanon is not a Muslim country even if its majority are Muslims, simply because its constitution dictates that Christians and Muslims remain equal. Anyway if you wanna talk about other countries, i think we should keep the dictatorships aside because those are countries that follow their dictator’s religion.

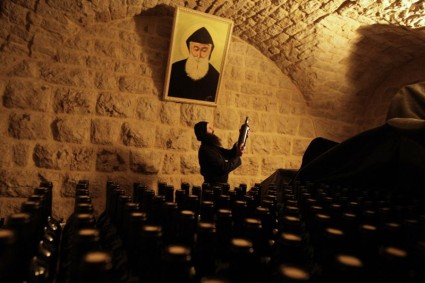

wow! such interesting article and comments especially the one from OH which was taken from the Economist apparently; I love that photo of the monk with Mar Charbel in the painting. Priceless.

Nagib,

I thought a country’s religion is defined by the religion claimed by most of its citizens (that how i remember i read the definition somewhere credible, need citations here!). But you are offering a very credible alternative that a country religion is defined by the religion claimed by the people running the country (This is sometimes applies to companies,i.e. a company is considered Lebanese if most of its C-suite is Lebanese even if the HQ is in London and most workers are Indian, http://www.hbs.edu/research/pdf/06-052.pdf )…I don’t want to talk about other countries, I was looking on how to define a country religion! Thanks for the brainstorm!

Michele,

I love your Lebanese spirit, Cheers to that!

Devin,

I think we should head out have a drink and discuss this whole country religion thing lol .. maybe Michelle can join us as well.

You did get my point nevertheless and the biggest example is Ataturk and how he changed Turkey to be a secular state and started his own “religion” so to speak. And turkey nowadays is fighting between going back to Islam or staying on Ataturk’s line.

Devin,

Countries don’t “have” religions! People follow one religion or another.

Najib,

Ataturk did try to establish a secular state; by name only. You could consult your Armenian, Greek and Assyrian friends about that! Christians have almost no rights in Turkey. Their churches have been looted and confiscated; their clergy killed and churches turned to barns. Do you call that secular?

Jeff,

You are right, I meant the religious identity of a country (as opposite to other identities for a state)! and in my first post I used nation but Lebanon is not a nation state far from it.

Jeff,

Ataturk also killed muslim clergy if i am not mistaken. I never claimed Turkey prevailed as a secular state, i just stated how Ataturk imposed a sort of religion of his own.

Umm .. Talk about prejudices ..

Just because my name is Ahmed Ramadan, that doesn’t make me a person who wrote a review about the wine without trying it. You should see my small bar back at my house.

Just because I wrote my story on Al-Masry Al-Youm, that does not make me Egyptian. I’m actually half-Syrian half-Lebanese.

Just because I said that in the middle east the main religion is Islam that does not mean Lebanon is considered Muslim.

I would like to ask you to read the original article, again, without the prejudice that you applied to my article before, then please feel free to email me with your views.

And Mostapha, thank you for noticing my intentions are good. Let’s talk about my own prejudice against drinking over a glass of wine when you come to Egypt, shall we?

I agree that anyone want to criticize he should start with his own country his own society which he know all about and involve in, criticizing other countries and different societies far from his present with shallow information taken from different media sources will lead to false un real opinions and also un wanted feedback from the criticized people.

Here I want to add something, anything I like or want and it is banned in my country sure I will search for it in other places such like alcohol. I like to drink because I like it and I enjoy it, not due frustration more I want to say long live Lebanon Country of all kind of people.

Lebanese are still looking for their identity:

Although I have my own opinion on the issue, there is no consensus yet over the ‘we are Arabs/Lebanese/Phoenicians’ debate.

According to your statistics, you just added another option:

‘We are Muslims, the rest are a meaningless minority’

Devin,

The Christians in Lebanon are sadly in denial. I agree with you and everyone else should as well.