I just finished reading “The Eternal Magic of Beirut”, an article by Michael Specter published on the NY Times. It’s one of the best articles I’ve read on Beirut in a long time.

Here are some of my favorite passages from the article but I highly recommend you read the whole thing.

On Beirut as a whole:

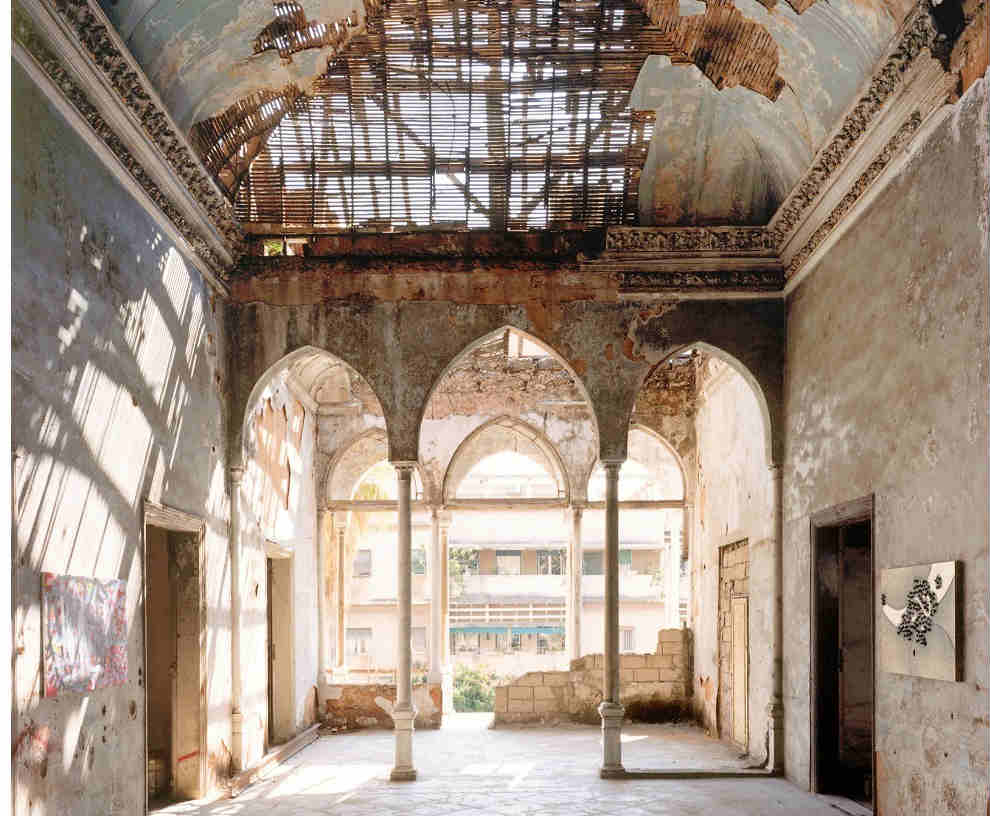

There is something singular about Beirut. It has one foot planted in the Middle East and the other in Europe, but it doesn’t quite belong in either place. Nothing seems permanent there; it is a perpetual transit point.

Perhaps alone among great cities, Beirut has earned, and manages to maintain, reputations both for wanton licentiousness and for utter terror. “There it stands, with a toss of curls and a flounce of skirts, a Carmen among the cities,” Jan Morris wrote in her great love letter to what she described as “The Impossible City.”

No other place could serve so effortlessly as a luxurious pit stop for rich Europeans, Arab royalty and celebrities like Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor. The cafes were filled with radical intellectuals, oil sheikhs and every kind of huckster.

On the ongoing crisis-mode we live in Beirut

Today, more than a million Syrian refugees have swarmed into the region, having fled the 10th-century carnage little more than 100 miles away. It is this constant tension that makes the city so hard to understand — and such a fascinating place to visit.

On Leaving Beirut

I asked if she ever considered leaving the city where she has spent the bulk of her life. “Of course,” she said. “But I don’t, and I am pretty sure I never will. This kind of turmoil, this kind of volatility, this kind of precariousness … ” She let the thought drift for a while. “I don’t want to say that life in war zones forces us to be creative,” she continued. “I know that is banal. But Beirut is a demanding city, and that makes it vital and alive. And vitality produces greatness.”

Villa Clara’s French Chef Olivier Gougeon take on Beirut

“Here, there is total anarchy,” he explained, with a look of pleasure in his eyes. “Chaos. You have to fight on a daily basis for everything you get.” And like so many others I encountered, he regarded that daily struggle as a benefit rather than an obstacle. “In France everything is regimented,” he said. “There are hours and rules and long vacations. Here there are no days off. And very little rest. But we have something they no longer have: energy, desire and complete freedom.”

On Solidere and the new souks:

The (Beirut) souks today are filled with shiny objects and marble floors. It is a great place to buy moisturizer, a $10,000 handbag or a Patek Philippe watch. But the new souks have far more in common with the Mall of America than with the many Levantine bazaars that have dominated the Arab marketplace for thousands of years.

There are cleaners, banks, bakeries and restaurants threaded through the old residential blocks. The newest towers, many of which hover ominously above graceful old villas, are nothing but giant walls of glass. Many terraces have been replaced with windows that can’t even be opened. “Every one of these places is a gated community, a vertical gated community,” he said. “There are no shops, no public space, no place to chat.”

On the US travel warnings to Beirut

But on the alert went: “U.S. citizens traveling or residing in Lebanon despite this Travel Warning should keep a low profile, assess their personal security, and vary times and routes for all required travel.” I did none of those things — nor was any of it necessary. There are parts of Beirut that are clearly unsafe; but tourists don’t, as a rule, hang out in Hezbollah-controlled territory. The city I visited was peaceful, even serene, and nobody I spoke to suggested it wasn’t. The loudest noise usually came from the most energetic nightclubs.

Reading these always makes me happy and proud. I wish the media in Australia can portray Lebanon in a positive light… they never do.

This is a nice summary of the article. I miss the energy of the cities there. The people, too. A good read, as always, Najib. 🙂